The Coming Showdown in the Race Crisis

Published in LOOK, July 16, 1963, pages 62-67.

Can moderation win over fierce emotions aroused by white-Negro relations in the U.S.?

By Harry S. Ashmore

Former editor, Arkansas Gazette. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the Sidney Hillman Award.

Photographed by Bob Adelman

IN THE FIRST CAPITOL OF THE OLD CONFEDERACY, a little backcountry politician leaned across a big desk and barked defiance at the United States of America. The law according to Gov. George C. Wallace provides that the Negroes of Alabama shall have only those rights the white majority sees fit to give them; any effort to change this condition of servitude, by Federal court order or peaceful demonstration, will be resisted, even though blood may flow.

In New York City, a slender Negro author emerged from a conference with the Attorney General of the United States and charged the nation's leaders with naive inability to recognize that massive racial violence impends not only in Alabama, but all across the land. The prophecy according to James Baldwin warns of a consuming fire, kindled by the white man's guilt, that could lay waste the whole of Western civilization.

These are the poles of an emotional charge that periodically shocks a complacent nation. They mark the new limits of an old issue. Somewhere in between lies the reality of the stubborn, complex social problem most Americans do not yet understand and can no longer avoid.

Governor Wallace can cause trouble, but he cannot prevail. The feudal system he seeks to maintain has been falling apart under its own weight for more than a generation. Now, he has been deserted by the responsible Alabamians who permitted, if they did not encourage, the intervention of his blue-helmeted troopers in Birmingham. Those whose power is recognized in the title Big Mules are still balky, but they have decided to get back to making money.

Mr. Baldwin can lend momentum to the drive for Negro rights, but he can produce neither the millennium nor the holocaust. His tortured eloquence flutters the intellectual, and his revolutionary words thrill the alienated of all complexions. The mass of American Negroes do not reject the existing social order, but seek only to share fully in its bourgeois blessings.

This does not mean that there is no prospect of a wholesale collision between whites and Negroes that could produce the first full-scale race riot in a generation. The spark of violence glows in every major city, and in most it is being systematically fanned. Yet, after nine years of rising tension in the wake of the Supreme Court's landmark school-desegregation decision, the great struggle so far has produced only the number of corpses normally handled by a metropolitan police morgue on a hot Saturday night.

This is hardly a statistic to be cited with pride. But, even if angry events were to revise the figure upward, the record would still stand as a significant measure of the gap between the rhetoric and reality of the crusade for Negro rights.

Actual, organized violence is in fact an unthinkable weapon for the Negro leaders. But the threat of violence is presently their most valuable tool, made doubly so, ironically, because it was first fashioned by their declared enemies in the embattled fiefs of Dixie.

In the beginning of the current struggle, doom-saying was used as effectively to inhibit Negro progress as it is now being used to promote it. John Bartlow Martin, returning from a tour of the region in 1957, entitled his report: The Deep South Says "Never!" He had reported what he had heard, and most of those with whom he talked believed what they told him – that the white folks would rise up en masse if a colored man set foot across the existing boundaries of segregation. The Eisenhower Administration held a similar view of the Southern temper and, in the critical early years, neither took action to implement the Supreme Court decisions nor uttered a forceful word.

The premise met its first real challenge in Little Rock, when Gov. Orval Faubus employed state troops to turn back nine Negro children from Central High School. The subsequent melodrama tended to obscure a revealing fact: Even with the Governor's strongly implied blessing, considerable effort was required to assemble a mob sufficient to overwhelm a small force of dispirited local policemen. Most of the leaders and much of the rank and file came from outside the city, and many were from out of state. The Arkansas mob had about as much spontaneity as the regiment of U. S. airborne infantry that arrived to clear the streets in a brisk action of 15 minutes' duration.

"Southerns are finding the price of segregation intolerable."

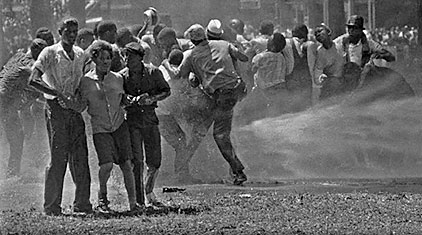

Negroes join hands to keep from being knocked down by water from the fire hoses used in Birmingham.

DESPITE THE MILES OF SHOCKING TELEVISION FILM, and the handful of demonstrators, U. S. marshals and reporters who have been blooded, this has been the basic pattern of every Southern encounter since. The Citizens Councils still attempt to nurture the delusion that the white people of the South are ready to resume the Civil War, and they continue to encourage mob action by predicting it. Most politicians and too many newspaper editors follow the line. Overtly or covertly, the bullyboys are urged to assemble wherever there is an impending showdown. But in New Orleans, the front line was reduced to snarling women, and their weapon was spittle. At Oxford, Miss., a rallying cry was sounded by a tragic ex-soldier from Texas. There was a stirring moment when Gen. Edwin Walker mounted a Confederate monument to harangue the crowd. But the thousands he had urged to march on Oxford didn't appear; it was a thin line that finally went against the tear gas of the marshals.

Superior Federal force and a demonstrated willingness to employ it obviously are controlling factors. But perhaps more significant is the absence of adverse mass reaction to such intervention. The psychological-warfare experts among the architects of massive resistance calculated that occupying Federal troops would solidify their support by stirring atavistic memories among the sons and daughters of the Lost Cause. Orators still cry out in the tone of Confederate bugles, but in fact the arrival of the Army has been greeted everywhere with a general feeling of relief that the situation is once again in hand.

There is not, in the end, any symbolic difference between a U. S. marshal's badge and a soldier's uniform. What counts is that every Southerner now must assume that sustained strife will bring in armed agents of the Federal Government, that they mean business and that there are more where they came from. Even when the resistance leaders fall back to the last resort of terror in the night, as the wilder ones usually do, they can no longer rely on sympathetic law-enforcement officers who look the other way. The ubiquitous FBI can't be reached or intimidated, and may have as many informers inside the Ku Klux Klan as it has in the Communist party. Little Rock's dynamiters were identified before the dust had settled and were in jail before the debris had been cleared.

The South's traditional capacity for unreality is such that these lessons could be taught only by demonstration. It has required a continuing assault to break down the elaborate Southern mythology that rested upon the assumption Negroes were really content with their lot and could be stirred to protest only by meddling Yankees. This belief served to ease consciences pricked by the unavoidable evidence of casual cruelty and pervasive inequity. On the practical level, it was used to support the argument of the old-time peace officers that a tough line was all that was required to put down any incipient unrest in "niggertown." The formula was simple, and had been effective in the past: Rap a few skulls, throw the ringleaders in jail and run the agitators out of town. Eugene (Bull) Connor fashioned a considerable political career out of Birmingham's misplaced faith in force. But despite the dogs and fire hoses and overflowing jail cells, the Negroes kept coming, and it was Bull who had to go.

The tragedy of the era lay in the emotional refusal of the Southern white people to recognize that times had changed, and so had the quality, the aspirations and the capacity of the Negro community. Those leaders who pointed to the evidence and pleaded for rational adjustment of the moribund social system were accused of treason and for the most part fell silent. Thus, by a process of elimination, the hard-core states elevated to power men who were ignorant or blinded by prejudice, or both. For ten years now, Southern legislatures, city councils and school boards have been largely engaged in the enactment of laws that were calculated exercises in bad faith. Lawyers of standing have grown rich manipulating legal technicalities in briefs that could succeed only if they were endorsed by an exchange of sly winks between judge and counsel.

This sort of moral corruption cannot be confined to the single issue of race, and there are signs of spreading rot at every level of government. In these terms, as well as in lost economic opportunity, Southerners are finding the price of maintaining segregation intolerable.

The Southern experience with the racial problem is unique only in detail and degree. The American dilemma had its focus in the region until recent years, and in important ways Southerners have been specially conditioned by their tragic history and their comparative poverty. Yet as the Negro population has spread across the nation and concentrated in big-city ghettoes, white Americans everywhere have displayed a comparable inability to come to grips with the moral issue and the practical problems posed by these second-class citizens. Wherever circumstances and geography have permitted, there has been a white retreat before the Negro invasion, and the Southern mythology, with its overtones of white supremacy and its unfounded obsession with miscegenation, has gained general currency in white suburbia. Where contact has been inescapable, there usually has appeared a familiar pattern of economic and social discrimination, calculated degradation and, at the extreme, hysteria.

IT IS AGAINST THIS BACKGROUND that Negroes have moved, in less than a generation, from the passive role of supplicants to active participation in a mass crusade against the form and substance of inequality. To this point, the tide of history has run with them, and they have been supported by the national conscience. Even in the South, the devotion of most whites to the status quo has been countered by a sense of personal guilt. At the ethical operating level, the United States Supreme Court has systematically translated the Constitution's libertarian spirit into the law of the land. Having won every critical test before the bar, Negroes can now carry their protest onto the sidewalks of the Deep South with the full protection of the Federal presence.

The parallel between Southern white resistance and the Negro crusade is striking and significant. One begot the other, and, substituting black for white, the language, the symbols, even the characteristics of the most conspicuous leaders and organizations are interchangeable.

At the far limits are the Ku Klux Klan and the Black Muslims – both ostensibly committed to the same declared aim, absolute segregation of the races. Both are secret societies that indulge in mystical, quasi-religious activities and rig up the faithful in uniforms. Both are ardent dues collectors. Both have a great fondness for parades and rallies and unbounded faith in their ability to intimidate their enemies. Both preach unbridled racial hatred and covertly encourage violence. Many of the past national leaders of the Klan have wound up in prison, usually on fraud charges, and Malcolm X., the most active of the Muslim apostles, is a former jailbird.

Or consider General Walker and James Baldwin. Both are men of education and attainment, fully endowed with the status symbols of their respective trades. Both came late to the racial battlefield, and have long been isolated from the rank and file for whom they now profess to speak – General Walker in the course of a distinguished military career, Baldwin in the years of literary exile that brought him deserved recognition as a writer. General Walker is unable to turn his back completely on his red-necked followers, or Baldwin on the Black Muslims, although both are obviously socially discomfited. Both deal with the race problem in stirring terms of personal, apocalyptic visions: General Walker sees the Visigoths of communism already over the walls, and Baldwin thinks a dark-skinned host has assembled at Armageddon. These revelations give each an exclusive patent on the verities. General Walker finds even so stalwart an anti-Communist as Sen. Thomas Dodd "blind" on home-grown subversion, and Baldwin believes Martin Luther King has reached the end of his rope.

The most notable political leaders also pair out neatly. Orval Faubus of Arkansas and Adam Clayton Powell of Harlem are wily old professionals who have found in the race issue the key to what appears to be permanent office. When he needs to be reelected, Governor Faubus simply hollers, "Nigger!" When Congressman Powell faces similar necessities, he cries, "Discrimination!" If this tends to cut them off from their political colleagues, who can't afford to say so, but with reason consider each a liability to his cause, it has its compensations. Powell is able to travel at public expense, and Faubus has the pleasure of operating the most comprehensive state political machine since the late Huey Long's.

"Orval Faubus and Adam Clayton Powell both see the race issue as the key to permanent office."

A Negro woman who was knocked down during a Birmingham demonstration is lead away by friends.

THESE AND MEN LIKE THEM have made most of the headlines that mark the steady progress of the Negro crusade. They are eternally ready to provide reporters with a harsh word and a dire prediction. They are in fact prime figures in the action and reaction, and the history of the period doubtless would have been different without them. Yet they are symbols, not leaders. They have been able to unleash powerful emotions, but the task of controlling the resulting force for coherent purpose has been left to others. For the white Southern leadership, the failure is clear and final: segregation cannot endure. For the Negro leadership, the test is only beginning.

It is at least possible that recovery from the emotional excesses of the recent past will serve to further reduce the incidence and virulence of Southern bigotry. In the period of convalescence ahead, white Southerners will be required to form new institutions and arrangements to replace those they can no longer doubt are unacceptable to their Negro neighbors. They have no real choice except to examine the possibility that they have nothing to lose and much to gain by seeing to it that Negroes reach their declared goals of increased economic opportunity and unlimited access to the facilities and amenities of the community. Not the least of the benefits could be the restoration of the bonds of genuine affection between whites and Negroes that enriched the older Southern tradition.

An increasing share of the burden of creating the necessary conditions for this development in the South, and for maintaining them in the North, is passing to the Negro leadership. The process that has contained the manifestations of white bigotry has encouraged the expression of Negro bigotry – and this has had inevitable response among a people whose grievances are real.

There has emerged a set of Negro myths as dangerous and as debilitating as their white Southern counterparts. The basic proposition here is that no white man can really understand how a Negro feels. This, in effect, accepts the argument of white racists that Negroes are inherently different. Since Negroes can hardly be expected to equate racial difference with inferiority, the result is the spurious doctrine of black supremacy long preached on the street corners of Harlem and now heard in more respectable precincts.

At its crudest, the Negro mythology has produced the Black Muslims and their effort to exploit the emotional response of American Negroes to the racial unrest that doomed colonialism in Africa and Asia. The identification of the Black Muslims with the true sons of Allah is about as valid as the Ku Klux Klan's claim to the traditions of the Scottish Highlands. Negroes have been in this country as long as any other Americans, and there has been no mass immigration since the slave trade was banned more than a century ago. The historic relationship of American Negroes to Africa is now devoid of cultural or religious significance. It is purely a matter of pigmentation, and this, as they discover at every point of contact with genuine African nationalists, is of minor consequence.

At a more sophisticated level, it is argued that the unique Negro experience under slavery and enforced segregation has had a purifying effect on those who suffered it. Baldwin, who oc-casionally seems to confuse himself with Job, gives the proposition a religious cast, contending that the black man represents a kind of original white sin, which, by means never made entirely clear, must be purged. Norman Mailer, Jack Kerouac and other avant-garde white novelists have attempted to distill out of the jazz, marijuana and uninhibited sex of the Negro Bohemian fringe the thesis that only alienation reveals ultimate truth.

THESE FANTASIES have led to public seizures of emotional segregation and have produced an outright attack on the older heroes of the Negro movement. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP is accused of selling his people down the river because there are white members on his board of directors, Adam Clayton Powell proclaims that Negroes cannot support any interracial organization that has white leadership. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who with considerable effect has devoted virtually his full time to service as advocate and negotiator for the Negro cause, is treated to derisive laughter simply because he is white. William Worthy, Jr., the controversial Negro journalist, has reached the remarkable conclusion that no white man can support the American Negro unless he also supports Fidel Castro. Here, as in the white South, passionate irrationality precludes effective discussion of the issue and of the practical means of resolving it. A leading Negro entertainer, shaken by the excesses of his peers, has privately confessed that he nevertheless has found it necessary to remain silent in order to avoid the dread epithet, "Uncle Tom."

The Negro mythology, like the white, constitutes a mirror image of reality. The degradation of the slums has crushed far more spirits than it has purified. Only the strongest members of any race emerge without crippling scars from a lifetime of deprivation, callous mistreatment and scornful abuse. That such individuals have now appeared in significant number to lead the marching columns of protest is a tribute to the older generation of white and colored leaders they have impatiently shouldered aside. It was the lonely battlers of the Urban League, the NAACP, the New Deal and the labor movement who brought about the reforms that freed many of the new generation from the ghetto and unshackled their militant spirit.

These dedicated young men and women, armed with pride and dignity, will find, if they look back, that they are still a minority among their own people. For most Negroes, the weight of oppression has eroded away the will and the capacity to seize the new opportunities and face the new risks. A high proportion have slipped irrevocably into the sloth and crime of slum life and constitute a social problem that is not affected by the argument that the fault is the community's, not theirs.

The Negro crusade, like any other, is fueled by emotion and does not welcome the dampening strictures of logic. As the only domestic social movement of current consequence, it has magnetic attraction for the sort of radicals and reformers who gave vent to their general protest against society by supporting the labor movement before the unions went flabby with success and affluence. For these, proud in their moral fervor, thrilled by vicarious martyrdom and comfortably removed from the scene of battle, the outcome of a given engagement is of little consequence. The situation is somewhat different for the tacticians in the field.

The most successful of these by far is the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Upon the solid base of the legal successes won by the now-eclipsed NAACP, he has promoted the mass demonstrations that have penetrated Southern resistance even in the final redoubts of Alabama and Mississippi. For the front-line leaders, it has been, and will continue to be, a delicate balancing act.

Dr. King needs the emotional voltage, and the financial support, generated by the firebrands at the great rallies in the North and West. But he also needs an open line, usually routed through the Department of Justice, to the white men who must issue the orders to desegregate. He can hardly file a public dissent when Prof. Kenneth Clark of City College of New York takes issue with Attorney General Kennedy and proclaims that the Negro people are no longer going to beg favors from the white power structure. But Dr. King is in Birmingham, and Professor Clark isn't, and it is Dr. King who in the end will sit down and negotiate the compromise settlement that will mark another step forward for the Negro people.

Considerations of strategy as well as his Christian devotion to nonviolence sent Dr. King into the poolhalls of Birmingham to remind the boys in the back rooms that switchblade knives provide no answer to the dynamite of white hoodlums. So long as violence is directed against Negro demonstrators, elemental standards of justice and Federal guns automatically are on their side. Let Negroes initiate the attack, or even reply in kind, and the balance will shift – and without this essential support, Negroes again will be a helpless minority in an aroused white community.

Martin Luther King not only subscribes to, but has given real meaning to, the battle cry of the movement: No white man has a right to ask a Negro to wait any longer for equality. But, as a practicing Christian, Dr. King also has to recognize that every white man has a right to insist that the quest for equality not be marked by a trail of blood.

It is on this critical point that Dr. King has had to part company with a good many of those who have lately swung aboard the freedom train. He speaks for justice. They cry out for vengeance. There was a moving, simple eloquence in the statement Dr. King's followers issued after a truce had been worked out in Birmingham: "The city of Birmingham has reached an accord with its conscience." All his adult life, Dr. King has preached and practiced in the service of a mission to unite a national community put asunder by the inhumanity of slavery and segregation. He could no more accept the mad design of the Muslims for a separate Negro state, or the admonition of the intellectuals who urge that bitterness be nurtured in the ghettoes of the mind, than he could join forces with George Wallace, Ross Barnett and Orval Faubus.

These are the surface elements of a racial crisis moving inexorably toward a showdown. All are the product of the tragic American failure to resolve the great moral issue that has tainted the nation's free institutions and truncated its ideals – the failure that once before led to fratricide.

It is, as Gunnar Myrdal has said, a peculiarly American dilemma. The Negro crusade has the sound of revolution, and many frightened whites and a few loquacious Negroes see it as such. Yet its goal is the opposite of that set by dark-skinned revolutionaries abroad, who seek to drive out their white rulers and shape their destiny on their own terms. Here, Negroes are demanding only admission to a closed white society that has imposed its standards while callously denying full access to its protections and benefits.

The demand is made as a matter of right, not as a device to create a new social order. It cannot be rejected, or further postponed, without still more damage to our diminished libertarian tradition and to our tarnished religious ethic. The high price the South has paid for intransigence is now being levied against the nation as a whole. The white community's effective abdication of moral purpose has produced a paralyzing failure of will on the part of the political leadership. Only now is there recognition that we can't get on with the nation's urgent business until we have begun, at least, to take care of the Negro's needs.

The Supreme Court, in splendid isolation, has discharged its responsibilities. The Court has defined the national policy forbidding racial discrimination and laid down the ground rules for its implementation. This should have brought Congress to the necessary business of fashioning new laws to replace those that have been swept off the statute books. Tangled in its antiquated rules, intimidated by the uncertain temper of its constituency, Congress has indulged instead in a fruitless decade of angry recrimination.

EISENHOWER HOPED until the end of his term that the race problem somehow would go away. Kennedy has understood that it will not, but he has given it low priority – and only now has he brought himself to use the full weight of his office to force the issue upon the lawmakers. If he succeeds, even if he only tries, we may be approaching the end of the long, costly season of default.

It is true that the ultimate solution will not be found in laws, but in the dark places of men's minds and hearts. But it is also true that laws are the manifest of the national purpose, and when government is unwilling, or unable, to provide them, there is no standard to which the wise and just may repair.

It is argued that the moderates have failed, and this is so. But it does not follow that moderation as a policy has failed. The fact is that it has not yet been tried. White, and now Negro, extremists have successfully blocked the scattered efforts to bring the leaderless mass of Americans to the kind of accommodations that will achieve harmony as well as justice. Yet this, surely, is the minimum essential, since Negroes and whites somehow must fashion the future on terms acceptable to both.

History and the peculiarities of our political system provide explanations, and even excuses, for our failure to live up to the moral imperative we have never denied. And the realities of the depressed Negro community make it clear that there will be no neat and orderly solution to social problems compounded by racial prejudice on both sides. But we have run out of options. The restoration of domestic tranquility demands nothing less than a renewed national commitment to the guarantees of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, this time without reservations. END