Death of an Innocent

What kind of mind could have planted the bomb that killed four children in Birmingham?

Published in LOOK, March 24, 1964, pages 23-25.

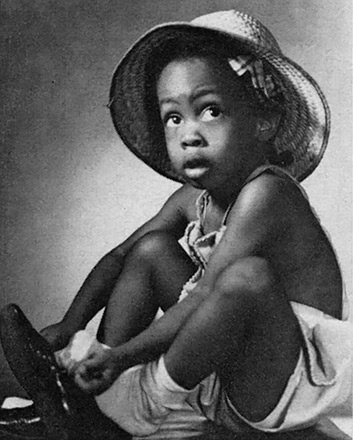

Carol Denise McNair, 11, one of the four bomb-murdered Negro children, never learned to hate.

By William Bradford Huie

Author of "Hiroshima Pilot"

SOMEWHERE IN ALABAMA, still free, lives the murderer of the child you see here. He murdered her inside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Chances are he never knew her, never saw her, yet he hated her enough to plant dynamite on a Saturday night and timed it to kill her next morning during Sunday school.

Her name was Carol Denise McNair. During her 11 years of life, I never knew her. But when, 70 miles from my home, she, with three other children, was murdered in church, I wanted to know her. And I wanted to understand her aspirations so that I could understand why her murderer wanted to kill her, what he could have against her.

I learned that until her head was crushed by falling concrete, Denise McNair had had a fortunate life. She was the only child of Mr. and Mrs. Chris McNair, two educated, aspiring, happy human beings who loved her and love each other. Both Chris and Maxine McNair are graduates of Tuskegee Institute; both are voters; both are valuable citizens of Alabama. Chris is a professional photographer, a good one. These pictures of Denise are his; he and I selected them from two hundred he made of his daughter during her lifetime.

Denise was also fortunate in her maternal grandparents. They are gentle, prosperous people, who operate a dry-cleaning business across the street from the church. Her grandfather found her in the church basement. He dug away the rubble and carried her to the ambulance, though he feared she was dead.

"I'm glad I found her," the grandfather said. "We loved her so much; and it seems right to find your own at such a time. There was so much screaming and running and confusion, so much terror, so much dust, and you could smell those dynamite fumes. I'll carry the memory of it to my grave, for I stand here every day and look across the street to where she died. But I'm glad I'm the one who lifted those big, sharp chunks of concrete off of her. My heart broke, but I'm glad it was me and not some stranger who found her."

She was raised with love and respect. It was difficult to explain racism to her.

MRS. MAXINE McNAIR told me: "I'm glad Denise never learned to hate. She knew she was colored, but she had white friends, and in her thoughts and playacting, she associated herself, not just with colored children, but with all children. She liked to watch television and go to movies. Jerry Lewis was her favorite entertainer. Because he raises money for muscular dystrophy, during the last week of her life Denise gathered the neighborhood children together and used my old dresses and put on a show and raised $13.81 for the Muscular Dystrophy Fund."

"The first movie that disturbed her was Giant," Mr. McNair recalled. "The children in it who were mistreated were Mexican-Americans, and Denise couldn't understand. We told her that a few white people don't like colored children, but we kept stressing that most white people like all children. 'And those white people who don't like us,' she asked, 'are they the old mean people like on television?' We answered yes, that was about the way it was.

"The first time she was personally hurt was a little later when she went with me to a five-and-ten store to buy some ribbon. Other children were eating hot dogs, so she wanted one. I tried to avoid explanation: I told her we'd soon be home where she could have chicken, but she forced me to tell her why she couldn't have a hot dog. 'Remember, Baby,' I said to her, 'what we told you about those few mean white people? Well, those few people don't want you to buy a hot dog in a five-and-ten-cent store in Birmingham, Alabama.' That made her cry. She was hurt, and I felt desperately angry and frustrated."

In Alabama, the state provides schoolbooks for the first four grades, and one of our ancient inhumanities is that our "basic readers" are illustrated only with happy white faces. In all the stories of Dick and Jane and Father and Mother and Spot the dog and Puff the cat and Tim the teddy bear, in all these stories with which children learn to read, the faces are white. This practice handicaps the emotional and intellectual development of our white children. But for our colored children, year after year, to have to learn to read about white children alone; for them, each year, to have to ask their teachers, 'Why don't Dick and Jane ever look like us?' – this is cruel.

But this cruelty was moderated for Denise. She attended Center Street Elementary School, one of Birmingham's better colored schools, where her mother teaches. Denise's parents bought her many books in which there are colored children. Denise also helped herself. For her playmates, she wrote and illustrated a story titled The Boy Who Wanted a Pet. The children in it are both white and colored, and the pet is a chicken.

The McNair home is a comfortable, well-kept bungalow. In it, Denise had her own room, her piano, her books, records and toys. She studied music and dancing; she was talented; and her parents had given her what the psychologists say every child needs: a good opinion of herself.

"Did you ever have to spank her?" I asked.

"Sure," Mr. McNair replied. "She was strong-willed, and I spanked her several times as she was growing up. From the day she learned to talk, she insisted' on being Denise, a unique personality. Some of this is good; we wanted to encourage it, but we insisted that she mind her parents. Her grandparents indulged her, like all grandparents."

Mrs. McNair smiled. "She was never a bad child. She was her daddy's girl – he indulged her, too. One thing: We didn't want her to be vain. The white people are not the only ones with a pigmentation problem. We have it, too. When colored children see only white children depicted as being comfortable,' the colored children are likely to want to be as white as possible. This can lead light-skinned colored children to discriminate against dark-skinned children. We taught Denise not to feel this way. And she became a champion of underdog children, whether they were light or dark, white or colored. She was always inviting children in to eat with her, and invariably she invited the underprivileged ones."

On the morning of her death, Denise McNair wore a three-quarter-sleeve, purple plaid dress of winter cotton. Her hair was in a French roll with a gold barrette. She wore white socks and black patent-leather shoes. She and her mother, who were Baptists, rode to church in the family car. Her father, who is a Lutheran, rode with his cousin to St. Paul's Lutheran Church. At 10:22 a.m., Mrs. McNair was sitting in the choir loft with her Sunday-school class. Denise was down in the basement with her class.

Denise's murderer was afraid – afraid of her abilities, afraid of her aspirations.

Denise, an intelligent, sensitive child, was always a champion of the underdog.

"IN MY Sunday-school class two miles away," Mr. McNair said, "we heard the noise at 10:22. We thought it was thunder; the day was overcast. I guess it was 10:45 before we learned that the Baptist church had been hit, and, I took off. As I approached the church, people were running everywhere, and police cars, ambulances and fire trucks were sounding their sirens. I stopped a man and asked, 'Did anybody get hurt?' He answered, 'You mean how many got killed!' Another man told me my wife was safe; he had seen her. Then my cousin drove up and said, 'Chris, we can't find Denise. We'd better go to University Hospital and see if she's there.' When we reached the hospital, we could learn nothing. Many injured children had been brought in, and we were told that some were dead. A hospital employee showed us a list of names, but Denise's name was not on it.

"My cousin and I were told to sit down and wait, and we sat in the waiting room and suffered. Finally, the employee came and told us to come with her. We were led to a room where four dead children were lying under sheets. I saw a little foot sticking out from under one of the sheets. A scarred patent-leather shoe covered with dust. I suppose every little girl's foot looks about the same, but I knew it was Denise. I didn't need to look under the sheet to know it was her. I looked ... and all I could do was stand there and choke and clench my fists."

Who murdered Denise McNair? The first answer is: a man who knows how to use dynamite and hates enough to murder.

Thousands of men in Alabama know how to use dynamite. They include miners, former miners, road builders, former servicemen and farmers who create ponds, blast stumps and dig basements and wells. Dynamite is an ideal hate weapon. It is cheap, readily available, simple to use; and planting dynamite at night requires no courage, entails little risk. It leaves neither fingerprints nor ballistic evidence, just impenetrable rubble.

Of these thousands who know how to use dynamite, I am informed that about 40 white citizens of Alabama are suspected of having participated in some way in 25 Birmingham "race bombings" since 1955. That was when the Montgomery bus boycott began. None of these suspects, as this is written, has been convicted of a bombing. (Recently, in Tuscaloosa, five National Guardsmen were indicted for exploding dynamite near the campus of the University of Alabama while they were guarding the student body against troublemakers. Two of them have pleaded guilty.)

"I didn't need to look under the sheet to know it was her."

One of the victims of this obscenely conceived, hate-poisoned bombing is carried off by rescue workers. Denise's battered body was discovered by her grandfathjer who has a cleaning shop across from the blasted church.

THE MURDERER of Denise McNair was an extremist among extremists. Men infected with race hate differ only in the sort of action they are willing to take to "protect" what they call their "way of life." All men who express hate with dynamite are willing to kill-if someone gets struck by the flying glass or stones. But those who toss dynamite may aim only to shatter glass and terrorize. Those who plant dynamite usually aim to kill. Denise's murderer wanted to kill. He probably had worked as a miner, since his estimated 16 sticks of dynamite were skillfully planted under concrete steps and were timed to explode when the building would be occupied. He knew just what he was doing.

But why did this murderer want to kill Denise? To answer that he hated her is not enough. Why did he hate her? Hate often stems from fear. He was afraid of her, afraid of her abilities, afraid of her aspirations, afraid of what she might do to his ego. A Southern white man who had murdered a colored man once asked me, "If I ain't better'n a damn nigger, what-the-hell am I better'n of?" Denise's murderer would ask me the same thing. He fears that one day he may be left with nothing more than a hound dog to feel "better'n of." Lacking other distinctions, he clings pitifully to what he thinks is a distinctive "white race." He needs to divide people into Us and Them. He needs to say, "We built good schools for niggers. Why can't they stay in their place? What do they want to associate with Us for?"

Of this, I am sure: Denise's murderer believes he did right. Like her, he is probably a Baptist, yet he felt he had to kill her. He may be reading what I say here, and everything I reveal about Denise will prove to him that he was right in killing her. His political idol, no doubt, is the Governor of Alabama, George Wallace. So I'll explain the murderer further by comparing how he thinks with how Wallace thinks.

Item: Even at six, Denise wanted to buy a hot dog at a five-and-ten-cent store. Her murderer would deny her this right. So would Wallace. The Governor would have white citizens boycott stores that sell hot dogs to both white and colored children. The murderer might reason that boycott alone may not prevent hot dogs from being sold to both white and colored children. Perhaps he thought a "murder lesson" was needed to "keep niggers in their place" and to "preserve the Southern way of life." The Governor also believes the "Southern way of life" must be preserved. But he opposes violence. The Governor and the murderer would agree on what needs protecting. They disagree only on how to protect it.

Item: If, at six, Denise wanted to eat hot dogs at a counter with white children, what would she have wanted by the time she was eighteen! She might have wanted to eat with white people at a downtown cafeteria! Or to sleep in the same motel as white people! Her murderer opposes this: He murdered Denise, hoping to prevent it. The Governor opposes it, but takes a different tack: The Alabama Sovereignty Commission spends my tax dollars-and Chris McNair's tax dollars-hoping to prevent it. The Governor and the murderer are in tactical disagreement.

Item: Denise didn't like the state's schoolbooks. She didn't want to learn to read only about white children. She created a story in which white and colored children play together. Isn't that Communist-inspired? Denise's murderer would think so; so does the Governor. The Governor and the murderer are both fighting communism. Their tactics are different.

Item: In future years, Denise would have registered to vote; never in her life would she have voted for a George Wallace. The Governor opposes colored people voting. The murderer made certain that Denise never votes.

Item: In her thinking and playacting, Denise associated herself not only with colored children, but with all children. She wanted to attend an integrated school. She thought she had something to give white children in return for what they could give her. Had she been allowed to live, she might have enrolled at Birmingham's best high school. One of the colored boys now in a previously all-white school in Birmingham is vice-president of his class. With her talents, Denise might have become a class president! Moreover, Denise would have wanted the best university education in Alabama. She might have wanted to study medicine and be an anesthesiologist – like those women doctors on Dr. Kildare and Ben Casey. There is only one medical school in Alabama – the university's Medical Center in Birmingham – and Chris McNair's studio is in the shadow of it.

DENISE'S murderer would oppose colored children and white children's going to the same school. So does the Governor. The Governor's announced plan is to keep fighting, keep resisting, keep up the pressure, and force the Negroes to drop out. The murderer had his own loathsome variation of-this plan.

Item: Instead of becoming an anesthesiologist, Denise might have become a skilled office worker and applied for a job with the State of Alabama. The Governor would oppose hiring Negroes to work alongside white office workers. So unquestionably would the murderer.

A final item: Denise's hero was the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. When Birmingham's colored citizens were demonstrating in the streets, fighting dogs and fire hoses last year, Denise begged her parents to let her demonstrate too. They refused, only on the ground that she was too young. Denise's murderer would regard Dr. King as Satan. The Governor said the King-led demonstrations were inspired by Communists. The murderer probably bombed a Sunday school to try to stop the demonstrations.

In Alabama, more than a million citizens, Negro and white, are revolted at the murder of Denise McNair. We regard her death as a senseless waste, a loss to the human race. We deeply regret that she was robbed of her future, for we did not fear her aspirations. We wish she could have had the opportunity to live her life at the highest level she was capable of achieving.

We believe that her murderer should be identified, tried and electrocuted. We are also ashamed of our Governor, and we believe he is hurting Alabama and all America.

I don't know how our other citizens feel. They are not articulate. The Governor claims he speaks for "the South" and for the majority of Alabama citizens. He doesn't. He speaks for himself. Many of the Governor's former supporters are obviously saddened by the murder. They may be uneasy over Denise's aspirations, but they seem to hope that the murderer can be identified and punished.

A few citizens still can't find it in their hearts to "blame the murderer much." They blame agitators, outsiders, homosexuals, Communists and Kennedys. They see Denise as a potential trouble-maker; and they see the murderer as a simple citizen, harassed by agitators, trying to "protect his children and his way of life." They want George Wallace to be President or, at least, to dictate who becomes President.

A number of citizens have contributed $80,000 to encourage identification and conviction of the murderer. I think they may as well take their money back. I don't think the murderer will ever be identified. For whenever authority shares the fears of a murderer, and condemns only his violent effort to relieve his fears, the murderer is seldom identified, almost never convicted. END