Lewis Marshall – "Selma: Turning Point for the Church"

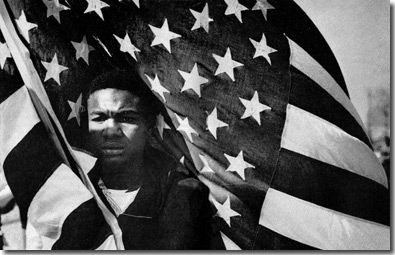

"A succession of marchers, like the youth at left [Lewis Marshall], carried American flags from Selma to Montgomery. The flags contrasted with the Confederate banners emblazoned on the jackets and helmets of federalized Alabama National Guardsmen along U.S. Highway 80." Photo by James H. Karales, March 1965. |

Lewis Marshall with the life-size sculpture of him at the National Park Service Selma to Montgomery Interpretive Center museum. Lewis didn't know that the museum had been built or that it had a sculpture of him until we took him there. Photo by Bill Ganzel, March 2012. |

|

|

Lewis Marshall was 15, growing up in Selma, in 1965 when a teacher of his in the segregated school told him about the effort to register blacks to vote in that predominately black county. Lewis started attending mass meetings that would announce strategies and demonstrations. "Growing up, I really wasn't around white people, and I didn't know about discrimination," Marshall says now. "The mass meetings taught me what I was missing, and I got very involved. I would sometimes just sleep in Brown Chapel after a mass meeting." For the Blood Sunday march on March 7th, Marshall was near the front of the group as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. He saw the police and sheriff deputies charge and start beating people. Somehow he escaped the chaos. He looked for a place to hide. The only possible hiding place was a sheriff's cruiser. He crawled in. Miraculously, the deputies didn't return or see him hiding. Finally, when the violence calmed down, Marshall was able to sneak back out and get back across the bridge. Marshall admits that he was so afraid of the beatings that he couldn't participate on the second march on Tuesday, March 9th. But shortly after that, white preachers, nuns and activists from the North began arriving in Selma to participate in the demonstrations and to bolster the ranks for the final march to Montgomery. It was the participation of church leaders that LOOK wrote about in their May 18th article, "Turning Point for the Church." "I figured that the KKK wouldn't shoot the white folks," Marshall says. "So, I found my courage." Others weren't so sure. Joanne Bland remembers her father telling her the white people were like targets. "You stood out like a sore thumb," she remembers. "We're black, right? And here we got all these white people who were called 'outside agitators' [by the segregationists]… So it became a joke in the project. You didn't lock the door until a white person was in the house. [She laughs.]" Still, Marshall felt safe enough that he was determined to walk the entire 54 miles to Montgomery. Under a federal court order, there were only supposed to be 300 marchers on the second through fourth days, so that they could be protected by federalized troops. Marshall was not among the 300 chosen by the leadership. But on the first day, he picked up a huge American flag. A friend picked up the other end so it wouldn't drag on the ground. He refused to lay the flag down when the leadership told him to go back to Selma. So they made him a "marshall" and he carried the flag all 54 miles. |

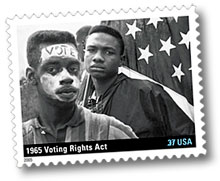

The photographs shot on the Selma to Montgomery march have continued to inspire others. Images of Lewis Marshall have ended on the covers of books and on a postage stamp. (The stamp photo is by Bruce Davidson.) In 2006, the National Park Service built the Lowndes (County) Interpretive Center museum half way between Selma and Montgomery. In one of the displays at this excellent museum, the curators reproduced an image of Lewis Marshall, along with a one-legged white marcher named Jim Letherer, in the room about the successful march. Lewis Marshall did not know about the museum or about the sculpture of himself until we took him to the Interpretive Center. He was overwhelmed with emotion. Soon, a video segment of Mashall discovering his likeness will be included on this page. In that moment, he was overwhelmed with emotion. The march, of course, was not the end of Marshall's life or story. After graduation, he received his draft notice, but he wanted to avoid being an Army "grunt" in Vietnam. So, he enlisted in the Air Force. He was trained as an aircraft mechanic. In an ironic and providential twist, his first assignment was in Vietnam … at Cam Ran Bay from 1967-68. Although he didn't see direct action, there was enough shelling of his base that he says he jumps when anyone comes up behind him and touches him. He knows he has some level of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). After Vietnam, the Air Force stationed him in Arizona – where he says he encountered racist attitudes – and then back home at Selma. Later, he and his wife were stationed in London, England, and they loved that posting. They had one son. Marshall is retired now and lives in Montgomery where he loves to hang out with his two granddaughters. |

|

|

||

The determination on his face and the visual impact of that huge flag attracted several photographers covering the march. He appears in several iconic photographs shot by photographers like

The determination on his face and the visual impact of that huge flag attracted several photographers covering the march. He appears in several iconic photographs shot by photographers like